Throughout last Saturday, July 6th, the future entrepreneurs Academic Working Capital 2019 participated in Online Interaction I, with lectures and moments dedicated to solutions development. The event is also one of the milestones of the program: it is when the groups leave the solution test phase and begin the problem test phase. Therefore, they need to decide whether to continue to invest in the current idea or to pivot, that is, to change the value proposition.

“If you maintain it, you proceed to the next phase of the program; if you want to continue interviewing, exploring new alternatives, you will pivot”, explained the program’s coordinator and master in Engineering Design, Diogo Dutra, and the designer Rodrigo Franco, AWC coaches. The groups were invited to explore the data they collected so far to understand if they had reached the ideal fit between product and customer, as well as estimating product price, costs and operating expenses, among other issues – that is. estimating “how much money is at the stake”. The result was presented to coaches and colleagues, who provided feedback and suggestions on the way forward. Those who decided to pivot, restarted the interview process and those who decided to maintain it, began the solution test.

Then, Artur Vilas Boas, coach and master in Entrepreneurship, presented the concept of MVP Minimum Viable Product, a process in which entrepreneurs build small versions of their products to see if there is public engagement with the idea. “It all starts in the hypotheses. From the hypotheses, how can I measure in an efficient way, and then, I build the experiment”, he summarized. Artur also gave MVPs examples, including companies born in previous AWC issues such as BeThink (2017) and HomeShelf (2018).

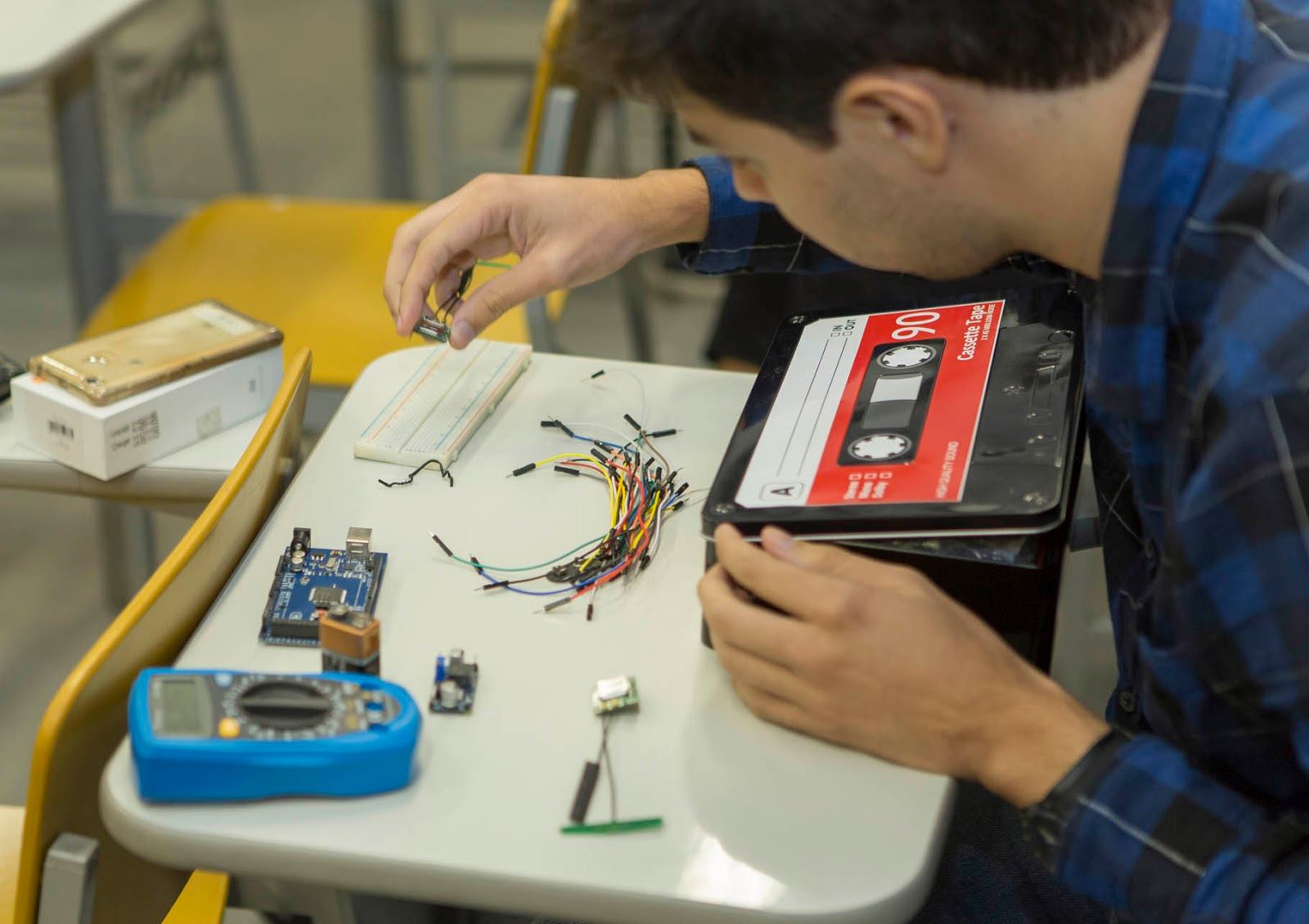

Coach Diogo Dutra explained that students need to transform value proposition into engineering requirements, into functionalities, so that a minimal solution generates maximum value. He explained three types of experiments: the napkin prototype, which can be done in 24 hours; the low quality, which can be done with own resources and automates part of the value proposition; and critical function, which seems more like the final product.

Ideally, at the end of this phase, the experiment will help some of the potential customers to become an early adopter (that initial client who agrees to use the solution, testing it and helping to improve it), something that has already happened with companies from previous AWCs: Road Labs (AWC 2017), with the napkin prototype; E-sporte (AWC 2016), with low fidelity prototype; and Mvisia (AWC 2015), with the critical function prototype.

The groups had time to present five napkin experiments based on their hypotheses and presented them to coaches and colleagues. To conclude, they attended a lecture from the engineer Pedro Fornari, from Road Labs, who told of the first sale of the startup. “It was very sudden. We went to do an interview and the guys said, ‘when can you deliver that to me?’ We went home and said: ‘I think we closed a sale there, we’ll have to deliver something”, he joked.

After that, AWC participants continue to work on the experiments and begin to prepare for Workshop II, face-to-face, which will take place on August 17 and 18 and will focus precisely on prototyping. By the end of the year, the groups should have done ten napkin experiments, ten low-fidelity, and one critical.